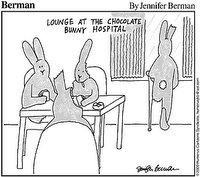

This is an interesting article, with a different take on chocolate bunnies, easter eggs, and the like. It quotes Susan Richardson, author of Holidays and Holy Days.

This is an interesting article, with a different take on chocolate bunnies, easter eggs, and the like. It quotes Susan Richardson, author of Holidays and Holy Days.As Richardson says, "the new Christian might look at a familiar symbol and see it with new meaning." For example, the hare, which has evolved into the modern day bunny, was seen as a symbol of fertility and spring. A Christian could view the hare?s coming out of the burrow, as representative of the burial and resurrection and a completely different form of "new life."Here is an oposing view:

As the early church began to expand into new lands, there were diverging opinions on how to handle local customs. One school of thought was to require converts to abandon their cultural traditions in order to embrace Christianity. Another tactic was to maintain local customs as much as possible but to give Christian meaning to them.

Richardson explains that the second strategy "was not an attempt to mislead, but more a cultural sensitivity to the people that were there." She says that this is much like the missionaries today who try to take the gospel and put it into context that is meaningful to people within their frame of reference.

I looked up Syncretism and Contextualization , and here are some good definitionsCan we imagine that God would be pleased with those that are commemorating the resurrection of His only begotten Son - on a day devoted to the worship of the sun.....or to a pagan goddess of fertility, Ishtar? In fact, God, the Father, has never asked His people to celebrate the resurrection at all - on any day of the week. A celebration of the resurrection is not taught in the Bible, but people do as they choose. They celebrate a day of their own making, in the way they please, while ignoring the request and example of their Savior.

The modern celebrations of Christmas (as celebrated in the northern European tradition, originating from Pagan Yule holidays), Easter and Halloween are examples of relatively late Christian syncretism. Earlier, the elevation of Christmas as an important holiday largely grew out of a need to replace the Saturnalia, a popular December festival of the Roman Empire. Roman Catholicism in Central and South America has also integrated a number of elements derived rom indigenous and slave cultures in those areas (see the Caribbean and modern sections); while many African Initiated Churches demonstrate an integration of Christian and traditional African beliefs. In Asia the revolutionary movements of Taiping (19th-century China) and God's Army (Karen in the 1990s) have blended Christianity and traditional beliefs.

The Catholic view is somewhat mediatied between contextualization and sycretismSyncretism is the reconciliation or fusion of differing systems of belief, as in philosophy or religion, especially when success is partial or the result is heterogeneous.

Syncretism can be contrasted with contextualization or inculturation, the practice of making Christianity relevant to a culture.

Contextualization is a word first used by linguists involved in communicating the translation of the Bible into relevant cultural settings. It was adopted formally by a gathering of scholars in the Theological Education Fund in its mandate to communicate the Gospel and Christian teachings in cultures which had not previously experienced them. Prior to the usage of the word contextualization many cross-cultural linguists, anthropologists and missionaries had been involved in such communication approaches such as in accommodating the message or meanings to another cultural setting.

The process of the Church's insertion into peoples' cultures is a lengthy one. It is not a matter of purely external adaptation, for inculturation "means the intimate transformation of authentic cultural values through their integration in Christianity and the insertion of Christianity in the various human cultures." The process is thus a profound and all-embracing one, which involves the Christian message and also the Church's reflection and practice. But at the same time it is a difficult process, for it must in no way compromise the distinctiveness and integrity of the Christian faith.

Through inculturation the Church makes the Gospel incarnate in different cultures and at the same time introduces peoples, together with their cultures, into her own community. She transmits to them her own values, at the same time taking the good elements that already exist in them and renewing them from within. Through inculturation the Church, for her part, becomes a more intelligible sign of what she is, and a more effective instrument of mission.

For me, what would seperate the sheeps from the goats is, "What is being worshipped?" If I answer "Jesus" and use the easter rituals to point to him, then I'd say that I am being contextual. It's a tough question, and missionaries have struggled with this notion since missionaries started taking the gospel to the world. I have heard various opinions at Acts 17 where Paul used the "Unknown God" to point to Christ. Some people say, it is a beautiful peace of rhetoric, but an example of what not to do. You should just preach the gospel. Others have used it as a reference point to saying Paul used a familiar item to point to Christ. We should too. Who's right? We do know that a few people wanted to know more and some got saved as a result of it. Do the ends justify the means?

Today, we say we are "culturally relevant." By this we mean that we addresses issues cultures deal with and integrate culture elements in our churches so that people don't seem disconnected from the world when they enter a church. In America, this may be rock music, lights, coffee, multimedia while in rural East Asia, it may be folk dacing, operas, and presentations on embriodery. Is this "in the world" or "of the world?"

What do you think?

Comments: 0

Post a Comment